Credit Sesame discusses the bank failures in March 2023.

Two high-profile bank failures dominated the news recently, and the fallout from those failures will continue in the days and weeks to come. The drama is far from complete. But, what we know of the story so far is of vital interest to anyone with a savings account. It also provides some clues as to what may happen next.

What’s happening with bank failures?

Within days, two significant US banks announced that they did not have enough cash available to meet the demands of depositors. This required the FDIC to step in and take over.

The Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank failed to meet their deposit obligations representing US history’s 2nd and 3rd largest FDIC bailouts.

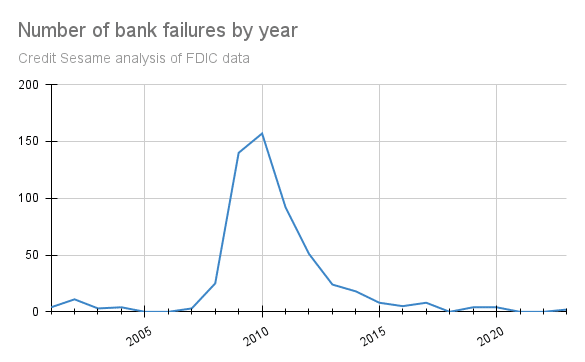

After several years of stability, bank failures are back in the headlines. Looking at the history of bank failures through the 2008 financial crisis and beyond puts the recent failures into perspective.

The chart shows the number of US bank failures from 2001 onward, according to figures from the FDIC. In the early years of this century, bank failures were unusual until 2008. That’s when the financial crisis took hold.

25 banks failed in 2008, followed by 140 in 2009 and 157 in 2010. That was the peak. Things began to settle down after that, with bank failures in the single digits for every year from 2015 on. There were no bank failures in 2021 and 2022.

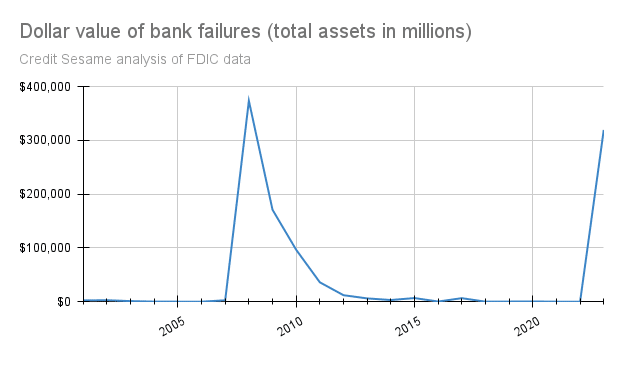

There have been two bank failures by the end of the first quarter of 2023. That may seem like a bad start for the year, but it is nothing too alarming from a historical perspective. However, when you look at the dollar value of the failed banks, it explains why those two recent failures have caused such a stir.

The two bank failures represented over $319 billion in assets. That means this is already the second biggest year on record for the value of bank failures. The year’s first quarter isn’t even over yet.

Why do banks fail?

While the FDIC measures the size of bank failures in terms of assets, the deposits are the key to understanding bank failures. A bank fails when it cannot refund customers their deposited money.

That generally doesn’t mean they’ve lost all that deposited money. It’s just that they don’t have enough immediate liquidity to cover the deposits customers are demanding.

When you deposit money in a bank, it doesn’t just sit there collecting dust in a vault. The bank invests the funds to finance operations, pay you interest on your money and turn enough of a profit for the effort to be worthwhile.

Banks use some of that money to make loans, while some is invested in securities, although banks are restricted to how much risk they can take with deposited money.

This means that from day to day, much of the money people have deposited in the bank is tied up in loans or investments. Under normal circumstances that’s okay, because only a small percentage of customers are likely to redeem their deposits at any given time.

Banks keep some cash in reserve to meet the portion of deposits their customers are likely to demand in the near term, while most of their assets are in loans or securities. Even if caught a little short, they can sell off some of their assets or borrow against them to meet depositor demand.

This model generally works smoothly, but the recent massive bank failures demonstrated a couple of things that can go wrong:

1. Mismatch between a banks assets and deposits

One of the things that usually makes banks profitable is that they can charge customers higher rates on loans than they pay out on deposits. They can also earn higher interest rates investing in government securities than the deposit rates they offer.

The rapid rise in interest rates over the past year messed up that model. Suddenly, banks had to offer higher rates to customers to attract deposits, while the money they lent was locked into lower rates for several years.

Also, rising interest rates depressed the value of even low-low-risk Treasury securities. While those securities pay their full value when they mature, they aren’t worth as much now because they pay less interest than current rates.

2. A large number of depositors demanding money back at once

One of the problems Silicon Valley Bank encountered was that many of its customers were tech companies. Recent months have not been kind to tech companies, and a lot of the venture capital money they rely on has dried up.

So, more of these companies started demanding cash. Once they realized the bank might have trouble coming up with that cash, the demand turned into a flood.

The role of FDIC insurance

FDIC insurance is intended to prevent that kind of panicked redemption of deposits. Historically, it has done the job pretty well. When people know a federally-administered insurance fund backs their deposits, they are less likely to rush to redeem their deposits when they suspect their bank may be in trouble.

What’s different this time?

In the past, FDIC insurance has helped maintain depositor confidence in their banks. It appears that in the case of Silicon Valley Bank, one reason depositors panicked anyway is that an unusual proportion of the bank’s depositors had more than the $250,000 insurance limit in the bank.

Because of its location and history, a large concentration of Silicon Valley Bank’s customer base was tech start-ups. They were using the bank to store very large amounts of cash. This glaring cash management negligence by some start-ups is less of a shock in the wake of revelations about practices at FTX.

Those uninsured deposits help explain why there was such a rush to take money out of Silicon Valley Bank when it ran into trouble. This is why the federal regulators announced they would cover even those deposits over the normal $250,000 limit.

Is expanding FDIC insurance a good idea?

This decision is something of a calculated risk. Regulators hope that by providing extra reassurance to depositors, they will stop the panic from spreading to other banks.

The reason this is a risk is that like all insurance, deposit insurance is funded by a pool of money that represents only a small fraction of the deposits it backs (1.27%, according to year-end FDIC figures).

That’s not as bad as it sounds. Even in the worst year of the last banking crisis, only 2.2% of banks failed. Banks that fail generally have a considerable amount of assets to offset a good chunk of the deposits they owe. So, the deposit insurance fund is usually sufficient to cover any shortfall.

The unknown factor is that by pledging to cover deposits of Silicon Valley Bank beyond the $250,000 limit, regulators have expanded the burden on the insurance fund well beyond what was intended.

Deposit insurance is funded by fees charged to participating banks. In theory, when the fund runs low, it can be replenished by raising fees. In practice, the more banks become distressed, the less able the banking system will be to afford contributions sufficient to prop up the deposit insurance fund.

What comes next?

What comes next is an orderly liquidation of the assets of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank to pay off deposits, with any shortfall covered by the FDIC fund.

Bank regulators will work with other distressed banks to help them find funding that would prevent them from reaching the point of failure. Expect to see an increase of merger and acquisition activity in the months ahead. There are currently about 4,700 FDIC-insured banks, so it is an industry that is ripe for consolidation.

There may well be some more bank failures, but as long as the pace of those failures can be contained the deposit insurance fund should be able to keep up.

Beyond that, it boils down to restoring confidence in the system. As long as depositors remain confident that their money is safe, the panic to redeem deposits will calm down. In the end, perhaps the most convincing argument for most depositors leaving their money in FDIC-insured banks is that though it may not be perfect, there really isn’t a safer option.

If you enjoyed Bank failures raise depositor concerns, you may be interested in,