If you’re comfortable using your fingerprint to pay for something with your phone, get ready for the next place where businesses want you to put your fingerprint — your credit card.

Mastercard® unveiled a credit card in April that has a sensor embedded in the plastic of the credit card. The cardholder can use a fingerprint, rather than a PIN or signature, to authorize payment. The card is being test marketed in South Africa.

Also called biometrics, the fingerprint sensor in the credit card is a follow-up to Touch ID, which has been common on iPhones since 2016 as a way to authorize payment with a fingerprint. Other kinds of phones also have the sensors.

While not everyone has a phone with fingerprint sensor technology, most people have at least one physical credit card. Seventy-two percent of U.S. consumers have at least one credit card, according to a survey by the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston.

Fingerprints aren’t the only way credit card companies are trying to make their products more secure. Computer chips with credit card information can be embedded in a keychain so a customer can complete a transaction without swiping or dipping a credit card. This and other innovations may or may not come to fruition as everyday payment methods.

Here are some ways that paying with a credit card may change in the future:

Overcome fingerprint flaws

A benefit of the biometric Mastercard® is that it works like any other chip card, according to the company. Merchants can use the same EMV card terminals that they already own.

Fingerprint sensors do have flaws. Hackers famously hacked the fingerprints of Germany’s defense minister using photos of her hands.

“While a fingerprint generally serves well, it is a one-time authentication that can be bypassed, with fraudsters having their malware activities after the fall back information or fingerprint has been entered,” says Yair Finzi, CEO of SecuredTouch.

Fingerprint sensors can’t be used in online transactions, Finzi says. Behavioral biometrics, wherein a user’s typical device interaction is analyzed, may be used more in the future to know that the user is who they say they are, he says.

“The future of fraud prevention lies in a more holistic approach to online authentication and overall transactional security, looking at the entire session, not just when the user demonstrates the right credentials — which may be stolen — or when a specific transaction is made,” Finzi says.

For example, behavioral biometrics can analyze how someone uses their phone, learning their patterns to improve the security layer. Finger pressure, finger size, touch coordinates, the angle you hold the device, and typing speed are among more than 100 physical behavior parameters measured.

Behavior is validated against a unique user profile, allowing real-time identity verification. The credit card company can choose a tolerance from zero to 1,000 (a score of 1,000 is a 100 percent confirmed customer) to approve the transaction. The higher the risk of the transaction — such as a high dollar limit or same-day payments — the higher the biometric score would have to be.

Change your credit card number — continuously

If your credit card is stolen, you may need to log into many online accounts where the credit card is stored to cancel the card and set up a new one.

The credit card issuer Final is trying to solve that problem by allowing cardholders to generate as many one-time-use or merchant-locked card numbers, along with a unique CVV (3-digit security code) number and expiration date, as they want. Cardholders would no longer need to depend on a single, static credit card number.

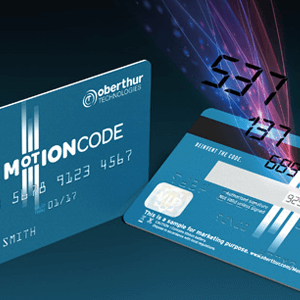

Rotating security code

Oberthur Technologies, which makes the majority of the chip cards in the U.S., has what it calls Motion Code cards with a mini-screen on the back that changes the CVV as often as 72 times every 24 hours.

The technology is similar to that of the Kindle, temporarily burning an image onto the tiny screen and then shutting off until it changes again. The card has a three-year battery life and is not thicker or bigger than a traditional credit card.

Once the number changes, any stolen credit card information is useless because it’s no longer accurate, according to the company, thus preventing fraud. The cards are being rolled out in Europe and are coming soon to the U.S., a company spokeswoman said.

Wearable credit

One credit card issuer launched its credit card in the United Kingdom more than 50 years ago, but how credit cards are used hasn’t changed much. Generally, the card itself is handed to a cashier or inserted into a reader, so that the number can be captured.

The company is now introducing technology to replace the plastic card with wearable items such as a ring, bracelet or keychain that contains a chip. Customers could buy something without stopping at the cashier to pay for it, according to the BBC.

The in-store technology will recognize that you’re there and will scan any products you carry out of the store, along with the payment information from your keychain.